The rise of DIY 3D-Printed Adaptive Gear is reshaping how athletes with disabilities access, customize, and afford performance equipment. In community labs, makerspaces and collaborative workshops, athletes and engineers are iterating on lightweight prosthetics, adaptive attachments, and sport-specific aids—cutting costs, accelerating personalization, and sparking fresh debates about safety and classification in elite sport.

From Prototype to Podium: Why Makers Matter

Traditional adaptive sporting equipment can cost thousands to tens of thousands of dollars, often leaving grassroots athletes without the gear they need to train at an elite level. Makers bring a different model: rapid prototyping, open-source design, and local fabrication. Community labs—Fab Labs, universities, and nonprofit makerspaces—offer access to 3D printers, CNC machines, and sewing tools plus a culture of shared knowledge. This lowers the barrier to entry and lets Paralympic hopefuls iterate on designs in collaboration with engineers and fellow athletes.

Cost Savings and Accessibility

- Affordable materials: PLA, PETG, and nylon allow for functional parts at a fraction of traditional manufacturing costs.

- Open-source directories: Repositories and maker communities publish STL files and assembly guides so athletes can reproduce or adapt designs.

- Shared resources: Makerspaces provide access to equipment and mentorship without the capital outlay required for bespoke commercial devices.

Customization: Built for the Athlete, Not the Catalog

One major strength of DIY 3D-printed solutions is fit and function tailored to an individual’s body, sport, and biomechanics. Athletes collaborate with designers to tweak socket geometry, adjust limb lengths, or add sport-specific interfaces—turning a one-size-fits-none approach into a personalized toolkit.

Examples of Custom Innovation

- 3D-printed grips and adapters that allow para-cyclists to control handlebars with limited hand function.

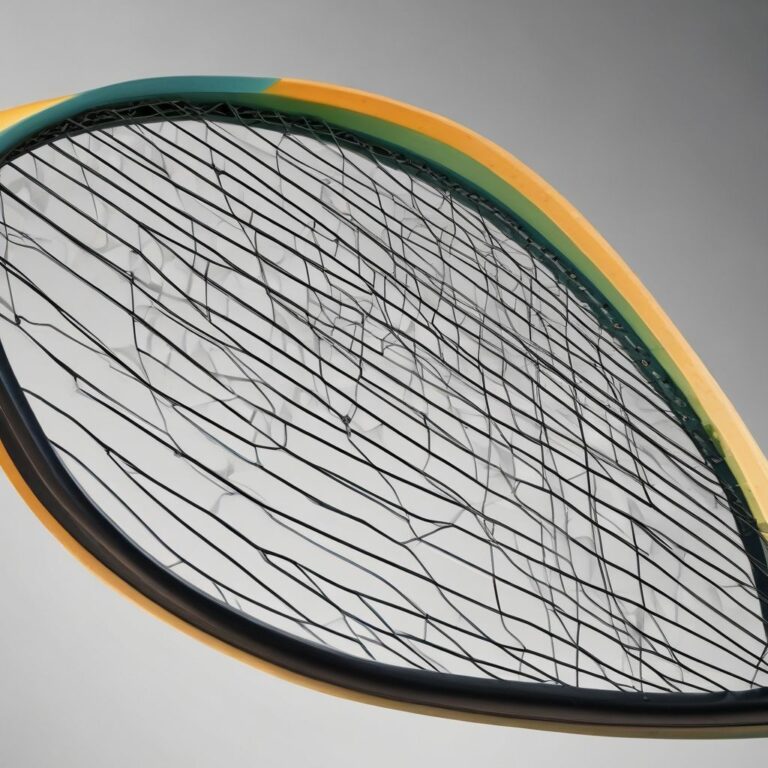

- Lightweight prosthetic covers and sockets optimized for running or throwing, balancing aerodynamics and comfort.

- Modular attachments that convert everyday wheelchairs into race-ready configurations for training and competition.

Inside Community Labs: Collaboration That Accelerates Improvement

Community labs act as crucibles for multidisciplinary collaboration—athletes, biomedical engineers, industrial designers, and physiotherapists converge around a workbench. The iterative loop is fast: test on track or court, gather athlete feedback, revise the CAD model, reprint. This human-centered design process shortens development cycles and embeds athlete agency in the engineering process.

Best Practices in Makerspaces

- Co-design sessions involving athletes at every stage to ensure function and comfort.

- Documented testing protocols—range of motion, load tests, and wear simulations—before full deployment.

- Material logs and print settings archived for repeatability and safety audits.

Navigating Classification and Safety Debates

As DIY 3D-printed adaptive gear improves performance, it raises valid questions for Paralympic classification panels and safety regulators. The balance between technological assistance and fair competition is delicate: how much mechanical advantage is allowed, and where does customization cross into enhancement?

Classification Challenges

- Standardization vs. personalization: Classification systems were built for traditional devices; bespoke gear complicates assessments.

- Transparency: Open-source designs can help classifiers understand intent and mechanics, but asymmetry in access may still confer advantage.

- Evidence-based evaluation: Objective testing—measuring energy return, stiffness, and mechanical advantage—must inform policy updates.

Safety Concerns and Mitigations

3D printing introduces variability: print orientation, layer adhesion, infill, and post-processing all affect strength. Without careful controls, a critical component could fail under competitive loads. To mitigate risk, community labs are developing standards: tensile testing, finite element analysis of designs, and third-party validation for competition-bound equipment.

Paths Forward: Policy, Partnerships, and Responsible Innovation

To harness the maker movement’s potential while preserving fairness and safety, stakeholders can adopt a few practical measures:

- Sport federations partnering with maker communities to co-develop evaluation frameworks and accepted material/process lists.

- Certification pathways for community-produced gear that include testing benchmarks and documentation requirements.

- Funding and mentorship programs that expand makerspace access in under-resourced regions, leveling the innovation playing field.

A Role for Open Standards

Open standards for file metadata, material properties, and test results would allow classifiers to compare devices transparently and consistently. When designers include measurement data alongside STL files, classification committees and engineers can make evidence-based decisions faster.

Real Stories: Athletes Shaping Their Own Tools

Across the globe, athletes are reclaiming design authority. A sprinter adjusts prosthetic stiffness for different tracks; a para-rower prototypes a custom oarlock adapter in a makerspace; a wheelchair racer iterates a low-friction push rim attachment. These stories share a common thread: empowerment through co-creation, where the athlete is both user and designer.

Conclusion

DIY 3D-printed adaptive gear—fueled by community labs and maker culture—offers a powerful route to more affordable, customized, and accessible sporting equipment for Paralympic hopefuls. To realize its promise responsibly, the movement needs shared testing standards, clear classification dialogue, and inclusive partnerships that spread access to innovation.

Interested in supporting local makerspaces or learning how to prototype adaptive gear? Join a community lab, or reach out to a local Paralympic organization to get involved today.