Mycelium Microfactories are emerging as a powerful solution to upcycle urban organic waste into bricks, insulation and consumer goods, and the concept is reshaping how cities think about materials, waste streams and carbon accounting. This article explores how fungal fermentation works at microfactory scale, profiles startups adopting the approach, and unpacks the technical, regulatory and lifecycle challenges that must be solved to make mycelium-based construction materials mainstream.

How mycelium microfactories work: the biology and the process

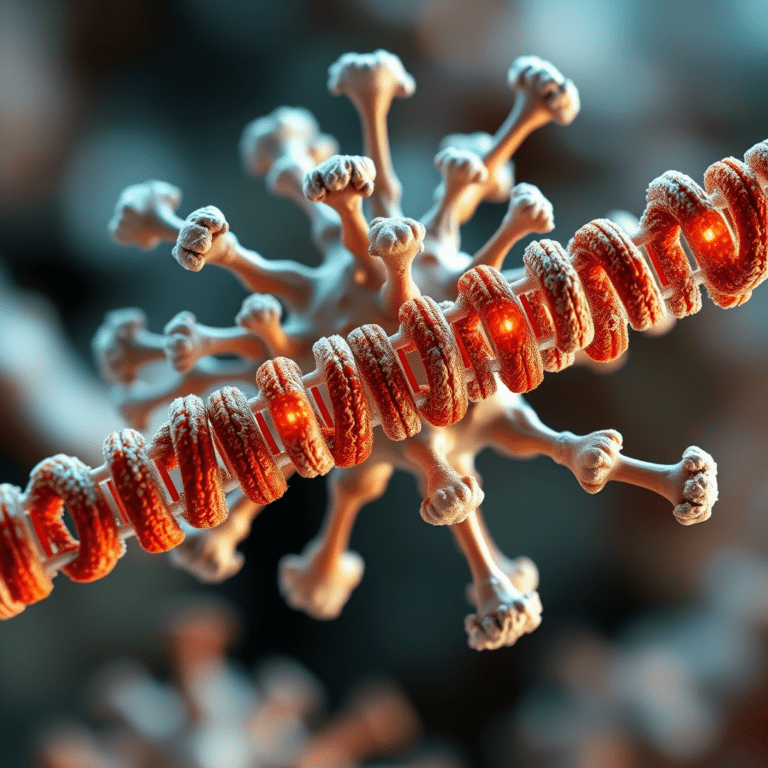

At their core, mycelium microfactories rely on filamentous fungal networks (mycelium) that colonize agricultural and urban organic residues to form rigid, foam-like composites. The basic production steps are:

- Feedstock collection and preprocessing: city food scraps, yard trimmings, spent grain or cardboard are shredded, pasteurized or sterilized to reduce competing organisms, and mixed to a consistent moisture and nutrient profile.

- Inoculation: prepared substrate is blended with mycelial spawn under controlled conditions to ensure even colonization.

- Molding and incubation: the mixture is packed into molds for bricks, panels or product shapes and incubated warm and humid until the mycelium binds the substrate into a solid form.

- Drying and finishing: fully colonized items are dried (and sometimes heat-treated) to halt growth, stabilize material properties, and reduce moisture to construction-grade levels; finishes or coatings are applied when needed for water resistance or fire performance.

This low-energy biological binding eliminates the need for Portland cement and petrochemical foams, creating a pathway to materials with significantly lower embodied carbon — and in well-managed systems, net carbon-negative outcomes through long-duration carbon sequestration in products.

Startups leading the way

A new generation of startups is building microfactories that operate near urban waste sources to shorten collection routes and embed manufacturing into neighborhoods. These companies differentiate by the feedstocks they accept, the product focus, and the technical systems they develop for scale:

- Bricks and masonry substitutes: mycelium bricks replace fired-clay or cement blocks for non-structural walls and landscaping pavers.

- Thermal and acoustic insulation: lightweight mycelium panels can rival polystyrene and mineral wool for insulation with better end-of-life options.

- Consumer goods and packaging: molded trays, furniture components and biodegradable packaging offer rapid commercial pathways with lower regulatory overhead.

- Hybrid composites: combining mycelium with recycled fibers or mineral fillers to enhance moisture resistance, stiffness or flammability performance.

Successful startups pair material science with operations: modular incubation units, automated inoculation lines, and quality-control analytics (moisture, density, compressive strength) to meet buyer requirements at scale.

Navigating standards, codes and acceptance

Taking mycelium materials from lab to building site requires navigating a patchwork of standards and codes. Because most building codes were written for mineral and synthetic materials, mycelium producers pursue several strategies:

- Certify products to existing standards where possible (ASTM-style tests for thermal conductivity, compressive strength, and fire resistance).

- Demonstrate performance in pilot projects and publish third-party test reports to convince regulators and insurers.

- Work with local authorities and green building programs (LEED, BREEAM equivalents) to secure pilot approvals and incentives.

Early wins often come from non-load-bearing applications—insulation, interior panels, acoustic ceiling tiles—where performance thresholds are lower and regulatory uncertainty is easier to manage.

Scaling: the microfactory model and urban logistics

Scalability is less about biology and more about logistics, reproducibility, and capital-efficient manufacturing. Microfactories address this by decentralizing production: small, modular production cells sited near waste generation points dramatically reduce transport emissions and keep value within communities.

Key operational considerations for scaling include:

- Feedstock consistency: blending city streams into predictable substrate recipes to ensure uniform product performance.

- Contamination control: robust pasteurization, clean transfer systems and microbiological monitoring to avoid failed batches.

- Automation and monitoring: sensors for humidity, temperature and growth progress plus digital traceability for chain-of-custody and carbon claims.

- Modular expansion: replicated production cells that can be rolled out city-wide without massive capital investments.

True carbon accounting: claims versus reality

Mycelium materials are often described as “carbon-negative,” but rigorous life-cycle analysis (LCA) is needed to validate that claim. Accurate carbon accounting must include:

- Emissions from feedstock collection and preprocessing (trucking, pasteurization energy).

- Energy used in incubation, drying and any post-processing steps.

- Displacement effects—what conventional materials are avoided and their embodied carbon.

- Biogenic carbon permanence—how long carbon remains sequestered in the product and whether it decomposes or is landfilled at end of life.

When microfactories use low-carbon energy, divert biowaste that would otherwise be landfilled, and produce durable products with long service lives, LCAs often show net climate benefits. Transparent third-party LCAs and conservative accounting methods are essential to build trust with regulators, investors and customers.

Challenges and opportunities ahead

Challenges remain: achieving water resistance without toxic coatings, meeting fire-safety requirements for certain applications, and securing stable demand beyond niche green buyers. Still, opportunities are significant:

- Cities seeking circular-economy solutions can partner with microfactories to lower landfill volumes and build local green jobs.

- Architects and developers can use mycelium materials to achieve low-embodied-carbon project targets.

- Policy incentives—waste diversion credits, low-carbon procurement rules—can accelerate adoption.

Practical tips for municipal and industry partners

- Start with pilot programs for non-structural uses to de-risk performance and approval pathways.

- Share feedstock data with producers to help them design consistent substrates.

- Require third-party LCA and material safety data to evaluate true environmental claims.

Mycelium microfactories are not a silver bullet, but they represent an elegant, biology-driven approach to converting urban organic waste into valuable, low-carbon building materials. With rigorous testing, honest carbon accounting and smart local partnerships, they can become a scalable element of circular urban infrastructure.

Conclusion: Mycelium microfactories combine biology, materials engineering and local manufacturing to create sustainable alternatives to high-carbon building materials; their success depends on solving standards, logistics and LCA challenges through collaboration between startups, cities and regulators.

Ready to explore how mycelium materials could fit into your project or city plan? Contact a local producer or request a pilot test today.