The rise of 3D-Printed Sprinting Blades is transforming how athletes with limb differences access competitive prosthetics—open-source prosthetics designs and local fabrication labs are lowering costs and accelerating innovation, forcing rulemakers to rethink fairness and regulation on the Paralympic track.

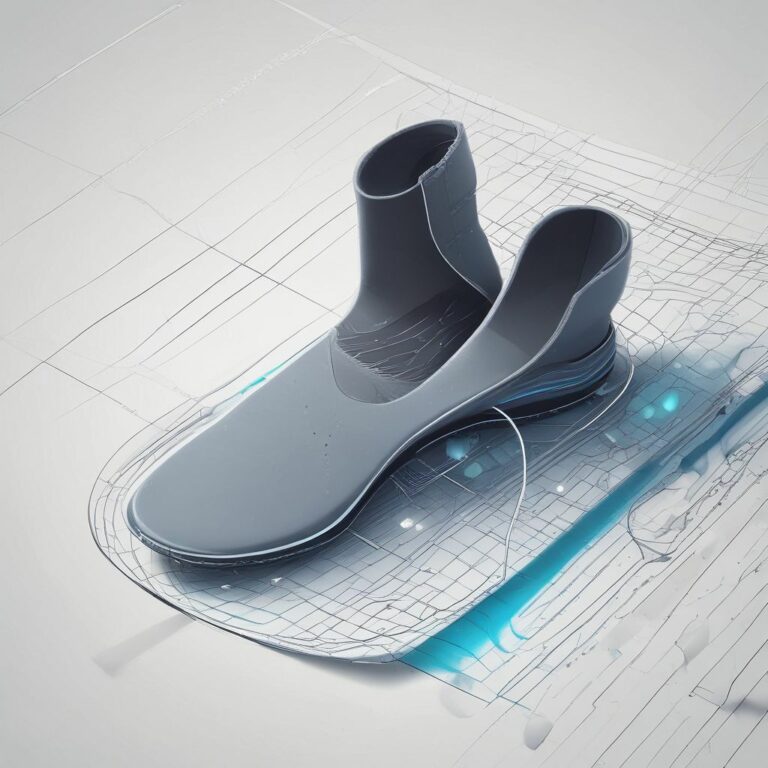

From Molded Carbon to Layered Polymer: A New Era for Sprinting Blades

For decades, elite sprinting blades were dominated by bespoke carbon-fiber manufacturing and deep-pocket vendors. Now, additive manufacturing, off-the-shelf composites, and parametric open-source designs have produced a new generation of 3D-printed sprinting blades that can be tailored, iterated, and produced locally. These developments compress development timelines and reduce price points, making sport-grade prosthetics accessible to athletes outside well-funded programs.

What makes 3D-printed sprinting blades different?

- Customization: Digital models allow for size, curvature, and stiffness to be adjusted per athlete and discipline.

- Rapid iteration: Designers can test new geometries and print prototypes in days, not months.

- Distributed production: Local fabrication labs (makerspaces, university fab labs) enable on-demand production near communities in need.

- Lower cost: While not replacing high-end carbon manufacturing for elite tune, 3D printing reduces entry costs dramatically for developing athletes and grassroots programs.

Open-Source Prosthetics: The Community-Driven Engine

Open-source prosthetics projects publish CAD models, material recommendations, and assembly guides, creating a collaborative ecosystem where clinicians, engineers, athletes, and hobbyists contribute improvements. Because the core designs are openly shared, innovations diffuse quickly—what starts as a tweak to improve energy return can become a global upgrade within weeks.

Benefits and ethical considerations

- Benefit — democratization: Athletes in low-resource regions can access competitive gear without waiting for expensive imports.

- Benefit — transparency: Open designs make it easier for researchers and regulators to evaluate performance characteristics.

- Risk — variability: Differing build quality across labs can create inconsistent performance between ostensibly ‘same’ designs.

- Risk — safety and liability: Without centralized quality control, improper manufacturing could harm athletes or skew performance.

Local Fabrication Labs: Bringing Production to the Athlete

Fabrication labs—community makerspaces, university engineering shops, and regional assistive technology centers—are the physical infrastructure enabling localized production. These labs provide trained technicians, safety-reviewed equipment, and often links to rehabilitation services. When paired with tele-design support and standardized testing protocols, local labs can deliver performance-calibrated blades that meet athletes’ needs quickly and affordably.

How labs are changing the landscape

- Proximity: Reduced shipping time and cost; blades can be tuned between training sessions.

- Capacity-building: Local technicians learn fabrication and fitting skills, creating sustainable service networks.

- Innovation hubs: Labs function as incubators where athletes and designers collaborate on sport-specific improvements.

Rulemakers and the Race for Fairness

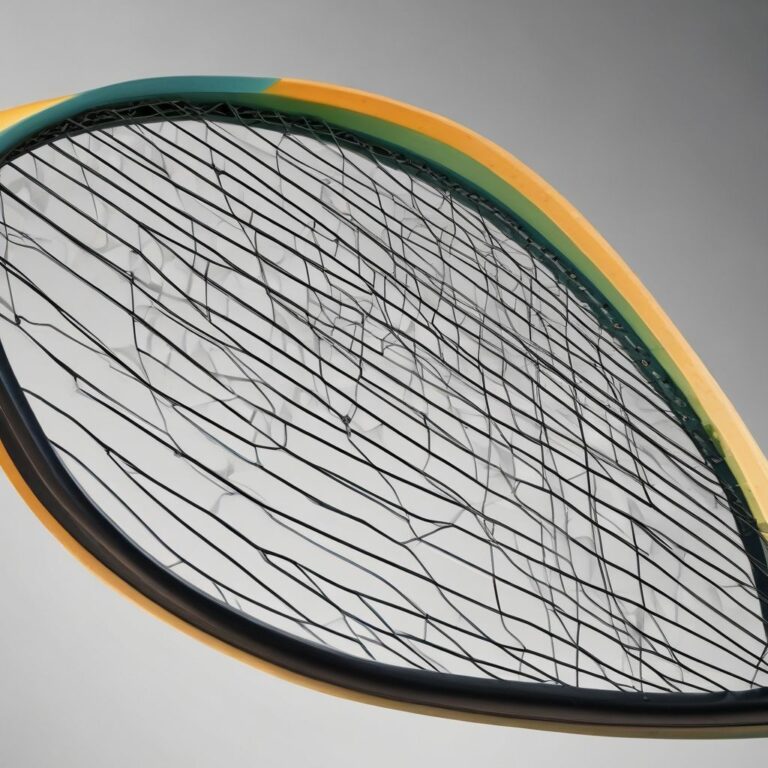

As alternative manufacturing lowers barriers, sport governing bodies face a dual challenge: ensuring fair competition while not blocking beneficial technologies. Paralympic and national athletics regulators must define where innovation enhances performance legitimately versus where it confers an unfair advantage beyond the athlete’s own capabilities.

Key regulatory concerns

- Performance parity: How to measure whether a prosthetic provides disproportionate mechanical advantage?

- Standardization: Should there be certification for materials, geometry, and manufacturing processes?

- Transparency and testing: Open-source models help, but consistent biomechanical testing regimes are required to compare blades reliably.

- Accessibility vs. elitism: Rules should prevent an arms race while protecting athletes’ rights to benefit from assistive innovation.

Examples of evolving approaches

Some federations are piloting tiered certification: prototypes undergo lab and field testing for energy return, stiffness, and safety before being approved for competition classes. Other commissions are forming advisory panels that include engineers, athletes, prosthetists, and ethicists to weigh trade-offs in real time.

Navigating Practical Challenges

Despite promise, adoption faces real hurdles. Quality control across decentralized labs is uneven, supply chains for high-performance filaments and composite materials remain constrained, and standardized assessment tools for comparing blades are still maturing. Addressing these requires coordinated action from multiple stakeholders.

Steps toward responsible adoption

- Create accessible testing protocols for energy return and stiffness that local labs can implement.

- Establish a voluntary certification program for labs and designs to build trust in distributed manufacturing.

- Invest in training programs for prosthetists and technicians in regions that lack expertise.

- Encourage open communication between innovators and rulemakers to avoid adversarial conflicts that slow progress.

Voices from the Track

Athletes who have tried 3D-printed sprinting blades report a mix of excitement and caution: excitement about affordability and rapid fit adjustments, and caution about long-term durability and regulatory acceptance. Coaches emphasize that, regardless of material, biomechanics, fit, and training integration remain the biggest determinants of performance.

Case study snapshot

In one community program, a university lab partnered with a Paralympic center to produce locally tuned blades for junior athletes. Turnaround time dropped from months to weeks, and athletes reported improved confidence and more consistent training loads. The program used a lightweight certification protocol and logged outcomes to inform future iterations—an approach now being replicated in several regions.

What’s Next: Toward an Inclusive, Fair Future

3D-printed sprinting blades won’t replace legacy manufacturing overnight, but they are reshaping who gets access to competitive prosthetics and how quickly innovations can reach athletes. The crucial task ahead is building robust frameworks—technical, regulatory, and community-based—that maximize benefits while minimizing risks.

When open-source design, capable local labs, and thoughtful rulemaking align, the Paralympic track can become both more inclusive and more equitable—allowing athletes to compete on merit, not on the accident of geography or budget.

Conclusion: 3D-Printed Sprinting Blades are accelerating access and innovation, but their long-term success depends on coordinated standards, transparent testing, and inclusive policy that balances fairness with opportunity.

Ready to get involved or learn more about local fabrication and certification pathways? Contact your regional Paralympic committee or nearby fabrication lab to find collaboration opportunities.